|

|

Home | Switchboard | Unix Administration | Red Hat | TCP/IP Networks | Neoliberalism | Toxic Managers |

| (slightly skeptical) Educational society promoting "Back to basics" movement against IT overcomplexity and bastardization of classic Unix | |||||||

|

|

| “You can fool some of the

people all the time, and those are the ones you want to concentrate

on.”

George W. Bush Gulling and milking the investor were taken as a matter of course, and the stock market was regarded as a kind of private casino for the rich in which the public laid the bets and the financial titans fixed the croupier's wheel. As to what would happen to the general run of bets under such an arrangement--well, that was the public's lookout, an attitude that might have been more commendable had not these same titans done everything in their power to entice the public to enter their preserve. --Robert L. Heilbroner, The Worldly Philosophers,

|

|

|

| The combination of

recent experience and a substantial body of finance research makes

a convincing case that there's no safety in owning stocks for 10,

15, 20, 30 years—quite the opposite Chris Farrell Rethinking Stocks for the Long Haul (Business Week, Feb 2, 2011 |

|

| If you retire at the "wrong" time, the downturn in stock market could be financially devastating for "long run" investors |

For the general public, it's a minefield out there. Wasn’t the original purpose of the stock market so that people could invest some money with companies that they thought might grow or at least generate steady income, in hopes of sharing in the rewards for the investment of their money? So historically stocks played role of junk bonds: more risky but more high dividend investments. Not anymore.

Seems very clear to me that this simple idea is now abstracted beyond any recognition into a giant casino game (with computer programs as major players), where actual companies really don’t matter much in driving the market up and down. HFT trading is now dominant and that means that all those old considerations about valuation, etc go to the tube in this epic struggle of trading robots trying to squeeze one cent or a fraction of a sent from somebody else orders.

Quants and algos and schemes like HFT seem to can exists only enough small fish exists in the cesspool. And its role in ecosystem is to be eaten by larger fish. The incredibly fast drop and bounce back on Thursday May 6, 2010 suggests that the computers must be driving most of stock market. In other words it is really a casino and individual investor can't win. Underlying fundamentals of the actual companies hardly matters anymore. While in Vegas, card counting can get you thrown out of the game to say nothing of using a computer to increase your chances to win while you are at the table, here it is a normal practice for large players. So the real question is not about return on your capital, but return of your capital. In other words zero rate of return (after inflation) is a big win for individual investor. And total return "in a long run" now is intrinsically linked not only to the long term performance of stock market but also to the strength of the currency

In other words life is unfair - and so are markets, especially if you’re a 401K investor brainwashed to hold all stocks portfolio. Both retail day-traders and retail "buy and hold" investors are royally fleeced by Wall Street: extremes meet. Both are plankton or small fish eaten by giant whales. There was a hilarious little book written by John Rothchild in 1988 A Fool and His Money: The Odyssey of an Average Investor written. At the very end of this book, Rothchild has a short glossary of major investment and stock market terms that he has defined as a result of his experience:

Deafening propaganda of "stock for long run" strategy asks for investigation of the efficiency "stocks for the long run" approach to 401K investing. The key question is "what stock prices reflect". And the answer is in the current situation they can reflect anything except the reality. That means that periodic crashes are given and that 401K investors who practice "faith-and-hope" based investing (which is more accurate term for "buy and hold") are to be burned.

First of all modern stocks prices are manipulated prices and in addition to Wall Street crooks the new powerful force of corporate stock price manipulation is the company executives (Reality, where art thou? by Martin Hutchinson Sep 30, 2009, Asia Times ) and, surprise, surprise, the US government.

A new webzine, CFOZone, has highlighted a study showing that companies that declare "pro-forma" earnings (dolled up by management to reflect the most-favorable assumptions) suffer increased attention from short sellers, about US$1.3 million worth initially after the pro-forma earnings declaration - just north of 1% of trading volume. This is good news; it suggests that the market is becoming hostile to attempts to fool it. The sooner we move to a reality-based capitalism, the better - but it may take some considerable time. [1]

Capitalist unreality takes numerous forms. Starting in the 1980s, it took the form of excessive reliance on mathematical models that did not work, such as the Black-Scholes options valuation model and the empire built on portfolio insurance before 1987. This caused a record-breaking one-day market meltdown, which itself was so far outside the predictions from the models as to render them obviously wrong. Yet the market continued to use them, preferring to wallow in computer-generated fantasy than to face up to reality.

....Needless to say, the ultimate triumph of faith-and-hope-based-investing was the dot.com bubble. Not only did valuations reach levels that could never be justified, but initial public offerings were carried out for companies that never should have existed. The central premise of Pets.com, that money could be made by express shipping cat food around the United States, was so foolish that a moment's reality therapy should have exposed it. In that market, no such reality therapy was possible.

At the opposite end of the scale, there was a notable increase in questionable and even fraudulent accounting. Enron and Global Crossing should have been put out of business by any competent auditor long before they went bankrupt. Their demise caused many to think that reality had once again dawned, but as we were to discover its triumph was to be a transient one.

As we now know, reality did not after all dawn in 2002. Instead, bureaucracy dawned (or blossomed) in the form of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act - legislation designed to improve standards for the boards of US public companies - while the Fed indulged in its unreality by fantasizing that the US economy was in danger of deflation. That delusion in turn produced the over-simulative monetary policy that gave us another unreality known as the housing bubble.

You might think that this is bad, you might think that this is good but the facts of the ground suggest that S&P 500 is monitored and in certain periods supported by the government.

Another important factor is that the term "other people money" (OPM) has very menacing meaning if we apply it to 401K financial intermediaries that manage our retirement savings. For all those financial professionals involved (fund managers, etc) it became very easy (and often profitable) to betray your best interests advocating the mode investing that is the most profitable to them, but can ruin your retirement.

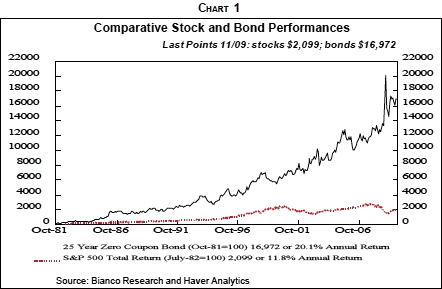

So it should not surprise you that for the 40-yr period ending last spring, 20-year Treasury bonds outperformed equities (Bonds Why Bother).

| Re-regulation of the financial services industry is long overdue and they should assume fiduciary duty for 401K Investments. Until this change be very careful and approach stock market and your 401K investments as you approach casino. |

Now couple of consideration about financial advisers. I would venture to say that the thousands of people who invested with Bernie Madoff believed they were using a "trusted adviser"? Re-regulation of the financial services industry is long overdue and they should assume fiduciary duty for 401K Investments. Until this change be very careful and approach stock market as you approach casino. We need clean the industry up first, before we toss our hard-earned money upon the caprices of rapacious wolves who were supported by powerful brain-washing by Wall Street PR machine, scamsters ironically hired using 401K investors own money... Here is one apt comment from Hank Paulson Held A Secret Meeting With Goldman Sachs In Moscow

grey on Oct 20, 6:10 PM said:

@GAZA: Gaza makes an important point here. In life, to fully understand something, one needs to try to look at things from as many angles as possible. The 'angle' that GAZA is referring to relook at the stock market from the insider's (or "seller's" if you will) point of view.

Over the past 40+ years, a common perception had grown that the "stock market" is the ideal place to put money for retirement. Well, ...

We all should have learned the true nature of these "wall street insider's" over the past two years ... scumbags who would sell their grandmothers into slavery for the cost of a sandwich. The thought that they care in the least about laws, honor, ethics is just laugh-out-loud funny. If they are selling you something, you can guarantee that it is very bad for you. They are selling stocks - so why buy from these dirtballs?

They not only would screw you out of your money in a heartbeat; that is what they do, all of them, all of the time. That is how they make their money. You are the sheep; they hold the knife, and they are addicted to your blood. Open your eyes and stop walking willingly towards the slaughterhouse. ReThink! Stocks are not "for the long run", nor for the short run, nor for any "run". Actually, run is a good term, as in "run in the other direction".

I predict, and apparently so does Gaza, that in short time, the common perception of the stock market as a wise place for investment will change drastically, and people will be no more likely to put their retirement savings in the stock market as they would to put it all on "Red" over in Vegas. Actually, that is not quite fair, since in Vegas at least you have the pretty lights ... and maybe free food ...

I am not yet a gold-bug, but I might be soon enough.

At the same time, in view of 2008 crash, I think that there is no place for small and 401K investors to hide. Just imagine that such crash happens to you the year you plan to retire. And the most dangerous thing is panic at the bottom. The latter became more probably, the higher percentage of stocks is in your portfolio and the closer you are to retirement. From this point of view 100-your_age formula might be too aggressive for people over 60.

At the same time "buy-and-hold" might be not the worst strategy, especially if buying is limited by some simple statistical metric (like professor Robert Shiller 10 year P/E ratio), anything that prevents buying at the top is OK. As buying "at the top" inevitably lead to multi-year stagnation of portfolio the key is when to buy, not how long to hold :-). With this reservation "buy-and-hold" looks like more palatable strategy.

Again, in no way this can be considered an investment advice as this is not my specialty and I not qualified in this particular field. I just try to understand it for myself and that are just my observations to which I came after doing some research on the subject.

The wisdom of holding stocks and bonds in a 401K portfolio came under fire in the 1990s. The rallying cry for this was the book Stocks for the Long Run of Wharton Business School Professor Jeremy Siegel The first edition appeared in January 1994, the second in March 1998 the third in June 2002 and, paradoxically, the forth in Nov 2007. The most influential was the second edition that was well timed to the dot-com boom. Despite dismal track record of "stock for long run" strategy for the last 5, 10 and 15 years recently it was translated into Portuguese language and published in Brazil.

1994 was a perfect timing for such a book as it was a start of dot-com bubble and the book quickly became a bestseller despite the fact the author proved to be hapless forecaster. The second edition of the book was published in 1998, two years before dot-com crash. And it was dot-com crash that demonstrated that Siegel really does know what he is writing about (which is pretty typical for economic professors, so in no way he is unique). While in no way the creator of this idea (he rehashed the ideas which were current before the Great Depression) Siegel mined gold in the heated atmosphere of dot-com bubble. Anyway, book is probably the most well known advocacy of this pseudo-scientific and semi-fraudulent recommendation to put most of your money (on our case 401K money) in "well diversified" stock index funds like S&P500.

We cannot repossess earnings from his book, despite the damage made, but at least we can use the term "Siegelism" for naive "all-stock" advocacy directed to 401K investors. In any case this "professor" did a substantial damage that is difficult to repair.

Ironically those years were the start the most damaging for stocks tendencies such as the start of looting of corporations by corporate brass, outsourcing, permanent decline of manufacturing base and hypertrophied growth of financial sector.

"Who needed bonds and cash?" rhetorically proclaimed well paid and totally unscrupulous stock entertainers (some with PhDs for extra credibility ;-). Stocks are the investment of choice. Bonds are so XIX century. Forget about the fact that stocks are just one asset class and an extremely dangerous one (fiat currency of a corporation). The financial industry is extremely good at telling people that they need to take on more risk in stocks and other exotic instruments, and the simple reason is that it serve's the industry's interest, increase the industry bottom line. As the industry is by and large parasitic it is who pays for those lavish salaries, obscene bonuses and plush offices. That's why mutual funds and investment banks embraced 401K plans as the Second Coming.

| The financial industry is extremely good at telling people that they need to take on more risk in stocks and other exotic instruments, and the simple reason is that it serve's the industry's interest, not the public's. That's why mutual funds and investment banks embraced 401K plans as the Second Coming. |

401K plans were tilted toward stocks and they served as great popularize of stock investments in the USA. They also lead to unprecedented growth of mutual fund industry. One additional factor that increases popularity of stocks is that broker fees which are essentially an entrance fee to the casino diminished dramatically starting from early 1990. In 1990 it was not uncommon to pay $30 to a trade executed via brokerage. In 2010 common fee was $5- $7.50. Also with the introduction of ETFs the fees that stocks mutual finds charges were dramatically cut. None of this factors changed the predatory nature of stock market itself but both did attract retail investors.

In addition there was "perma-bull" flavor of this propaganda that proved to be very effective in brainwashing 401K investors. In 1999, the S&P 500's annual return topped 20% for an unprecedented fifth consecutive year. Jeremy Siegel published his second edition of his tremendously harmful book "Stocks for the long run" in 1998. It was extremely good timing and the second edition was a real bestseller.

Like is the case with cults, dot-com bubble bust did not discredit the "stock for a long run" strategy. Many royally fleeced 401K investors remained believers in their guru. And Siegel personally remained quite popular.

| "Any fool can buy a company.

You should be congratulated when you sell." Henry Kravis |

Discussion of using stocks for 401K investment portfolios is often based on historical data. Here is one pretty revealing chart that some 401K investors should probably tattoo on any suitable part of the body in order to diminish inclinations to do stupid things or assume that Wall Street allow them to earn positive "after inflation" return in stock market casino.

This is a pretty devastating chart for "stocks for the long run" crowd. But real situation is even worse: historical stock returns and stock vs. bond trends are meaningless. And not only because of Goodhart's law. There were tremendous changes in the operation of both public corporations and stock exchanges (which now include new players such as hedge funds and government connected vampires like Goldman Sacks) for the last 50 years, which accelerated staring with Reagan presidency.

As Patrick Hosking noted in Times on Oct 29, 2008( Turbulent times test our faith in equities) Siegelism is just a pseudo-scientific and semi-fraudulent approach, masking attempt to sell you something by using academic terminology (Vanguard played an important role in promoting Siegel's investment philosophy) :

It is an article of faith among most investors that equities outperform government bonds. Smart long-term investors put their money in shares because over any lengthy period in the past century or more, they have produced much bigger returns than bonds have.

With shares now languishing unloved once more, that faith is being put to the test. The cult of the equity is still the mainstream view but its adherents are having to be a lot more patient than usual. British shares are lower today than 12 years ago. Japanese shares are lower than 26 years ago. Tim Bond, the man behind Barclays' Equity-Gilt study, has crunched up-to-date numbers for The Times and come up with some sobering findings. Only investors who put their money to work in 1983 or earlier would have done better placing it in equities than government bonds (gilts). From 1984 onwards, in any timeframe up to the present day, gilts have produced a better total return than shares. Over any timeframe of less than 15 years to the present day, even deposit accounts have produced a better return.

The hefty premium that supposedly rewards investors prepared to take the extra risk of investing in shares has not paid off for anyone with a time horizon of less than 25 years. In short, capitalism has not been working terribly well of late.

... ... ...

Some argue that the notion of the free lunch given to long-run holders of equities is plain wrong. The idea that the risk of holding equities declines the longer one holds them is a fallacy, the skeptical minority say. If it were so, then the cost of an equity put option - an insurance policy against markets failing to rise to an agreed point - should decline the longer the time frame. It doesn't. No one among the rocket scientists on the big bank trading desks - for all their fancy stochastic modeling techniques - is keen to take that side of the bet.

It's clear that diversification in stocks and holding them for long time, two key postulates of siegelism, do not ensure a profit or protect against a loss in a declining or stagnant market. But what is interesting they do not outperform bonds in a booming stock market too if we are talking about 10 year scan or longer. For 10 years, 20 years, even 40 years, both TIPs and ordinary long-term Treasury bonds have outpaced the broad stock market.

"Most observers, whether bond skeptics or advocates, would be shocked to learn that the 40-year excess return for stocks, relative to holding and rolling ordinary 20-year Treasury bonds, is not even zero,"

That means that for retirement savings a simple approach like 100-your_age formula to stocks/bonds allocation is preferable to "stock for long run" strategy. So better strategy does exists and it is simple enough to follow for any investor and at the same time, as my simulation experiments have shown, is competitive with more complex strategies for considerable number of randomly chosen 30 year historical periods (I used random starting dates from 01/01/1960 to 01/01/1980, S&P500 for stock portion of portfolio and 10 year bonds for bond portion). You can use junk bonds instead of S&P500 as they are highly correlated. TIPs can be used as bond part if available. In any case, it is important to understand that the question now is not return on capital, but return of capital so average annual returns is very misleading metric.

In 2008 S&P lost nearly in half of its value, something many buy & hold cheerleaders admit is possible, but it is supposed to a very rare, one is a hundred years, occurrence. For those who planned to retire this year it was really nasty surprise.

Looks like it can be much more frequent that that and as we have seen "buy and hold" crowd was decimated in 1972-1973, 2001-2003 and again in 2008. These once in a hundred year disasters seem to come along with disturbing regularity and much higher frequency. As "buy and hold" the cornerstone of Siegelism, Professor Siegel credibility, or what was left from it after 2002, was called into question.

In a WSJ article Jason Zweig puts together a devastating critique Does Stock-Market Data Really Go Back 200 Years? , showing that book assumptions are and its methodology is statistically invalid:

“There is just one problem with tracing stock performance all the way back to 1802: It isn’t really valid.

Prof. Siegel based his early numbers on data first gathered decades ago by two economists, Walter Buckingham Smith and Arthur Harrison Cole.

For the years 1802 through 1820, Profs. Smith and Cole collected prices on three dozen banking, insurance, transportation and other stocks — but ended up including only seven, all banks, in their stock-market index. Through 1845, they tracked 19 insurance stocks, but rejected 95% of them, adding only one to their index. For 1834 onward, they added a maximum of 27 railroad stocks.

To be a good measure of stock returns, an index should be comprehensive (by including many stocks) and representative (by including the stocks commonly held by investors). The Smith and Cole indexes are neither, as the professors signaled in their 1935 book, “Fluctuations in American Business.” They cherry-picked their indexes by throwing out any stock that didn’t survive for the whole period, whose share prices were too hard to find or whose returns seemed “inflexible,” “erratic,” or “non-typical.”

Thus, Siegel’s basis for Stocks for the Long Run exclude 97% of all the stocks in the early history of the US market by cherry picking winners, ignoring survivorship bias, and engaging in data mining. As a result he managed to considerably juiced the returns of stocks "in a long run". The era of 1802-1870 ended up with a much bigger dividend yield then it should have had. Siegel originally started at 5.0%, but over ensuing versions, that crept up to 6.4%. The net impact was to raise the average annual real returns during the first half of the 19th century from 5.7% to 7.0%. If you artificially raise the initial returns in the early part of the data series, then the final annual returns also become much higher. As Zweig sardonically notes, “Another emperor of the late bull market, it seems, has turned out to have no clothes.”

The stock market is not a place for honest people to hang out.

From theoretical standpoint "stocks for a long run" 401K strategy belongs to the class of "naive" investment strategies. The term "Naive Diversification" was introduced in the paper Naive Diversification Strategies in Defined Contribution Saving Plans in regard to so called 1/N strategy:

This paper examines how individuals deal with the complex problem of selecting a portfolio in their retirement accounts. We suspected that in this situation, as in most complex tasks, many people use a simple rule of thumb to help them. One such rule is the diversification heuristic or its extreme form, the 1/n heuristic. Consistent with the diversification heuristic, the experimental and archival evidence suggests that some people spread their contributions evenly across the investment options irrespective of the particular mix of options in the plan. One of the implications is that the array of funds offered to plan participants can have a strong influence on the asset allocation people select; as the number of stock funds increases, so does the allocation to equities. The empirical evidence confirms that the array of funds being offered affects the resulting asset allocation. While the diversification heuristic can produce a reasonable portfolio, it does not assure sensible or coherent decision-making. The results highlight difficult issues regarding the design of retirement saving plans, both public and private. What is the right mix of fixed-income and equity funds to offer? If the plan offers many fixed-income funds the participants might invest too conservatively. Similarly, if the plan offers many equity funds the employees might invest too aggressively.

Here we extend the term to the whole class "stock for the long run" investment portfolios. 401K investors should understand clearly that the conventional wisdom of investing in stocks "for a long run" (Siegelism) is by-and-large myth and urban legend.

|

401K investors should understand clearly that the conventional wisdom of investing in stocks "for a long run" (Siegelism) is by-and-large myth and urban legend. |

Now let's discuss why Siegelism is semi-fraudulent approach to investing and is very damaging to you if you are on receiving end of this nonsense. As after 2008 debacle the tone of mainstream media changed commentators start accusing investors of reckless behavior while in reality in was Wall Street which lured unsuspecting public into this giant Ponzi scheme (as of May, 2008 with S&P 500 at 905, 401K investors who invested 100% in S&P 500 using cost averaging with by-weekly contributions since Jan 1, 2006 lost approximately 45% in comparison with 401K investors who invested 100% in stable value fund.)

For example in Recession’s End Won’t Make Investing Easier Jane Bryant Quinn wrote at Bloomberg.com:

Odds are that you’ve been over-invested in equities. At the end of 2007, almost one in four workers between the ages of 56 and 65 held more than 90 percent of their 401(k) in stock, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute in Washington. More than two in five held more than 70 percent in stock. They will be well into Social Security before recovering their losses.Maybe these 401(k) holders managed their risk by owning a bond portfolio on the side, but I doubt it. More likely, they’re investing aggressively, in hope of making up for the fact that they started serious saving late. They gambled and lost. The market is no respecter of your personal need to make money in a hurry.

First of all, if returns of stocks "in a long run" is higher then average returns "in a short run", this should affect not only options (as noted above), but also bond market -- especially long bonds. This topic was well covered in the paper by Professor Zvi Bodi On The Risk of Stocks in the Long Run Professor Bodi came to the following conclusions:

This paper examines the proposition that investing in common stocks is less risky the longer an investor plans to hold them. If the proposition were true, then the cost of insuring against earning less than the risk-free rate of interest should decline as the length of the investment horizon increases. The paper shows that the opposite is true even if stock returns are "mean-reverting" in the long run. The case for young people investing more heavily in stocks than old people cannot, therefore, rest solely on the long-run properties of stock returns. For guarantors of money-fixed annuities, the proposition that stocks in their portfolio are a better hedge the longer the maturity of their obligations is unambiguously wrong.

... ... ...

A critical determinant of optimal asset allocation for individuals is the time and risk profile of their human capital. A person faces an expected stream of labor income over the working years, and human capital is the present value of that stream. One's human capital, is a large proportion of total wealth (human capital + other assets) when one is young, and eventually decreases as one ages. From this perspective, it may be optimal to start out in the early years with a higher proportion of one's investment portfolio in stocks and decrease it over time as suggested by the conventional wisdom.

... ... ...

It is often pointed out that investing in bonds exposes the investor to inflation risk — the risk of depreciation in the purchasing power of the currency in which the bond payments are denominated. One straightforward way to address this problem is to denominate the bonds in terms of a unit of constant purchasing power. Indeed, the governments of the United Kingdom and more recently Australia and Canada have issued long-term bonds linked to an index of consumer prices with precisely this purpose in mind, i.e., to offer investors a safe way to eliminate both interest rate risk and inflation risk over a long horizon.

One sometimes gets the impression from reading popular articles on stocks as an inflation hedge, that their authors view stocks as if they were long-term real bonds. But there is a very big difference between stocks and long-term real bonds. With real bonds, the investor knows that regardless of what happens to the price of the bond prior to its maturity date, at maturity it will pay its holder a known number of units of purchasing power. With stocks there is no certainty of value — real or nominal — at any date in the future.

In the academic finance literature, researchers investigating whether stocks are an inflation hedge in the long run usually hypothesize that real stock returns are unaffected by inflation in the long run. By this they mean that the real return on stocks is uncorrelated with inflation. They do not mean that stocks offer a risk-free real rate of return, even in the long run.

That means that not stocks but TIPS should be the cornerstone of any 401K portfolio, as they hedge against inflation risk that most important risk in fiat currency world and at the same time have much lower default risk and volatility. It is stupid (idiotic might be a better word, if the investor is close or over 50 ;-) to keep dominant part of your 401K portfolio in stocks. The exception might be 401K investors who can afford being glued to financial data a couple of hours each day and thus can benefit from arbitraging large stocks movement (usually 401K plan provides a certain amount of reallocations per year; often one or two which can be used for this purposes).

The key dogma of naive Siegelism is that you just need to contribute enough money using cost averaging into well diversified index (for example S&P 500 or, better, Total Market Index) and self-regulating market will take care about the rest. You just do not need bonds or money market funds except may be TIPS. But there are risks that he failed to mention and first of all that past returns are a good predictor of the future, especially as the time was unique. The turmoil we are experiencing in 2008 is just a symptom of a structural change which signifies end of easy credit connected with a huge wave of liquidity unleashed since 1990 (market fundamentalism or "socialism for the rich").

Stock market and indexes such of S&P500 over the last twenty years produced good returns with modest volatility. But one can argue that this was not only due to technological revolution (computers and Internet) but also due to easy credit wave launched after the dissolution of the USSR with the dollarization of huge territory with half billion of new consumers provided the USA as owner of the world currency unique opportunities. In that environment, passive investing became the standard. But in 2001 this trend seized to exit. Still the Fed waved dead chicken for another six years and pushed value of houses though the roof due to easy credit. Creation of derivatives especially CDO and CDS (Credit Default Swaps) make bad situation even worse.

| Long-term investing in stocks may have worked before the market became a giant casino, but it is no longer is applicable or safe. In casino capitalism stocks are tradable instruments for speculators, who parasite on 401K investors because they create for them the platform for short selling. |

Long-term investing in stocks may have worked before the market became a giant casino, but it is no longer is applicable or safe in the world of casino capitalism. Now stocks are tradable instruments for speculators, who BTW parasite on 401K investors because they create for them the platform for short selling. Given the tremendous uncertainties regarding future cash-flow, interest rates and other economic factors, there is obviously little justification for relying on any simplistic metrics like P/E to predict stock prices.

Psychological factors may play a greater role in stock prices than economic variables. among them :

Fraud recently is another important factor that is definitely is not in 401K investor control. Most financial reports are semi-fraudulent and companies go to great length to cover the real situation under the garbage pile of inventive accounting. Also any business entity that requires continued infusions of outside (often in the form of stock issuance) of new capital to function on an ongoing basis is a Ponzi scheme. ( in the spirit of Minsky's Instability Hypothesis).

This is why there is so much marketing pressure from MSM for middle class to continue to fund the stock portion of their 401K retirement accounts.

Stock market historically demonstrated "recurrent Ponzi-scheme" pattern with boom followed by busts. Few people can play Warren Buffet and as soon as returns are too good to be true get out and don't worry about missed gains. In his long post to Naked Capitalism blog Leo Kolivakis, publisher of Pension Pulse depicts the level of corruption that is associated with "cult of equities" (Guest Post: A Giant Experiment?)

In late January, Pensions & Investments published an article, PBGC Premium Boost. I quote the following:

The agency’s huge deficit and Mr. Millard’s desire to avoid any eventual PBGC taxpayer bailout spurred the most significant contribution during his tenure: a major change in the agency’s asset allocation policy in February 2008 that permits the agency to invest up to 10% of the $55 billion it has available in private equity and real estate. Both are new asset classes for the PBGC.

Under the new asset allocation, designed to close the PBGC’s deficit over the next 10 to 20 years, 45% of assets will be in equities, 45% in fixed income and 10% in alternatives. Previously, 75% to 85% was in fixed income in a strategy designed to match assets with liabilities. The remainder was invested in stocks.

Some critics have charged the new asset allocation is too aggressive for an agency that is supposed to backstop failed private pension plans. But Mr. Millard said the new policy has a far better chance of closing the PBGC deficit than the previous policy did.

“I would urge people to recognize that it is a long-term policy, and that PBGC’s liabilities will last for decades, and we need an investment policy that focuses on the long term,” Mr. Millard said.

Today, the Boston Globe reports that the pension insurer shifted to stocks (also, read Yves' post below):

Just months before the start of last year's stock market collapse, the federal agency that insures the retirement funds of 44 million Americans departed from its conservative investment strategy and decided to put much of its $64 billion insurance fund into stocks.

Switching from a heavy reliance on bonds, the Pension Benefit

Guaranty Corporation decided to pour billions of dollars into speculative investments such as stocks in emerging foreign markets, real estate, and private equity funds.The agency refused to say how much of the new investment strategy has been implemented or how the fund has fared during the downturn. The agency would only say that its fund was down 6.5 percent - and all of its stock-related investments were down 23 percent - as of last Sept. 30, the end of its fiscal year. But that was before most of the recent stock market decline and just before the investment switch was scheduled to begin in earnest.

No statistics on the fund's subsequent performance were released.

Nonetheless, analysts expressed concern that large portions of the trust fund might have been lost at a time when many private pension plans are suffering major losses. The guarantee fund would be the only way to cover the plans if their companies go into bankruptcy.

"The truth is, this could be huge," said Zvi Bodie, a Boston University finance professor who in 2002 advised the agency to rely almost entirely on bonds. "This has the potential to be another several hundred billion dollars. If the auto companies go under, they have huge unfunded liabilities" in pension plans that would be passed on to the agency.

In addition, Peter Orszag, head of the White House Office of Management and Budget, has "serious concerns" about the agency, according to an Obama administration spokesman.

Last year, as director of the Congressional Budget Office, Orszag expressed alarm that the agency was "investing a greater share of its assets in risky securities," which he said would make it "more likely to experience a decline in the value of its portfolio during an economic downturn the point at which it is most likely to have to assume responsibility for a larger number of underfunded pension plans."

However, Charles E.F. Millard, the former agency director who implemented the strategy until the Bush administration departed on Jan. 20, dismissed such concerns. Millard, a former managing director of Lehman Brothers, said flatly that "the new investment policy is not riskier than the old one."

He said the previous strategy of relying mostly on bonds would never garner enough money to eliminate the agency's deficit. "The prior policy virtually guaranteed that some day a multibillion-dollar bailout would be required from Congress," Millard said.

He said he believed the new policy - which includes such potentially higher-growth investments as foreign stocks and private real estate - would lessen, but not eliminate, the possibility that a bailout is needed.

Asked whether the strategy was a mistake, given the subsequent declines in stocks and real estate, Millard said, "Ask me in 20 years. The question is whether policymakers will have the fortitude to stick with it."

But Bodie, the BU professor who advised the agency, questioned why a government entity that is supposed to be insuring pension funds should be investing in stocks and real estate at all. Bodie once likened the agency's strategy to a company that insures against hurricane damage and then invests the premiums in beachfront property.

Since he issued that warning, he said, the agency has gone even more aggressively into stocks, which he called "totally crazy."

The agency's action has also been questioned by the Government Accountability Office, the investigative arm of Congress, which concluded that the strategy "will likely carry more risk" than projected by the agency. "We felt they weren't acknowledging the increased risk," said Barbara D. Bovbjerg, the GAO's director of Education, Workforce and Income Security Issues.

Analysts also believe the strategy would not have been approved if the government had foreseen the precipitous decline in the stock market.

Now, they warn about a "perfect storm" scenario in which the agency's fund plummets in value just as more companies go into bankruptcy and pass their pension responsibilities onto the insurance fund. Many analysts say it is inevitable that the agency will face significantly increased liabilities in coming months.

"The worst case scenario is coming to pass," said Mark Ruloff, a fellow at the Pension Finance Institute, an independent group that monitors pensions. He said the agency leaders "fail to realize that they are an insurer of pension plans and therefore should be investing differently than the risk their participants are taking."

The Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation may be little-known to most Americans, but it serves as a lifeline for the 1.3 million people who receive retirement checks from it, and the 44 million others whose plans are backed by the agency.

The agency was set up in 1974 out of concern that workers who had pensions at financially troubled or bankrupt companies would lose their retirement funds. The agency operates by assessing premiums on the private pension plans that they insure. It insures up to $54,000 annually for individuals who retire at 65.

Despite its name, the agency does not necessarily guarantee the full value of a person's pension and is not backed by the full faith and credit of the government.

Nonetheless, agency officials say that if the pension agency fails to meet its obligation, the government would come under intense political pressure to step in. That means taxpayers - including those who don't get pensions - could be asked to pay for a bailout.

Currently, the agency owes more in pension obligations than it has in funds, with an $11 billion shortfall as of last Sept. 30. Moreover, the agency might soon be responsible for many more pension plans.

Most of the nation's private pension plans suffered major losses in 2008 and, all together, are underfunded by as much as $500 billion, according to Bodie and other analysts. A wave of bankruptcies could mean that the agency would be left to cover more pensions than it could afford.

In the early years of the George W. Bush presidency, the agency took a conservative investment approach under director Bradley N. Belt, who favored putting only between 15 and 25 percent of the fund into stocks.

Belt said in an interview that he operated under "a more prudent risk management" style and said he "would have maintained the investment strategy we had in place." Belt left in 2006 and Millard arrived in 2007.

Under Millard's strategy, the pension agency was directed to invest 55 percent of its funds in stocks and real estate. That included 20 percent in US stocks, 19 percent in foreign stocks, 6 percent in what the agency's records term "emerging market" stocks, 5 percent in private real estate and 5 percent in private equity firms.

Millard said he thought he had little choice but to seek a higher investment return in part because Congress had limited the agency's ability to charge higher premiums based on each plan's likelihood of drawing on the agency's funds.

The agency's board - which consists of the secretaries of Treasury, Labor, and Commerce - approved the new investment strategy in a meeting in February 2008. But the board members have had only a limited role in the agency's operation, meeting only 20 times over the 28 years before 2008.

The board is also too small to meet basic standards of corporate governance, according to an analysis by the Government Accountability Office.

"The whole model of having three sitting Cabinet secretaries with day jobs overseeing a $60 billion investment portfolio and occasionally owning significant percentages of large American companies is fundamentally flawed," said Belt, the former agency director.

The Government Accountability Office is preparing a new review of the investment policy, but in the meantime it continues to place the agency on its list of federal programs at "high risk."

And the article above brings me to another excellent post by Ian Williams that appeared on the Barricade blog over the weekend, Who Killed U.S. Public Pension System?

Ian was kind enough to email me and share his insights with me. The charts above are from his post and I quote the following:

Professor and Nobel Laureate Paul Samuelson in late 1998 was quoted as saying, a bit sadly, “I have students of mine - PhDs - going around the country telling people it’s a sure thing to be 100% invested in equities, if only you will sit out the temporary declines. It makes me cringe.”

When someone tells you that stocks always beat bonds, or that stocks go up in the long run, they have not done their homework. At best, they are parroting bad research that makes their case, or they are simply trying to sell you something.

Which leads nicely into our 2nd bullet point - politically connected pension systems promising benefits and COLA’s assuming and I am likely being conservative a 7.5% investment return assumption on their portfolio which is now skewed heavily into stocks over bonds. Their investment return assumptions are PIE IN THE SKY or RAINBOW PONIES WITH WINGS depending which fantasy reference you prefer. I think it is time for pension systems to allocate 200% into equities with leverage provided by the US Govt as the retirement and pension systems are woefully underfunded.

The misleading numbers posted by retirement fund administrators help mask this reality: Public pensions in the U.S. had total liabilities of $2.9 trillion as of Dec. 16, according to the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. Their total assets are about 30 percent less than that, at $2 trillion. With stock market losses this year, public pensions in the U.S. are now underfunded by more than $1 trillion.

I urge to read Ian's entire post and to start taking a closer look at how your pension funds are being managed or mismanaged.

The solution to the pension crisis won't be easy. But we have to start by admitting that the crisis exists and that pension funds have not taken adequate steps to address their underfunded status. Only then will we be in a better position to confront the challenges that lie ahead.

Another argument for a stock for along run approach is usually related to pseudo-scientific (Lysenkoist, to be exact as it serve powerful interests) notion known as efficient market hypothesis. with Here is how Wikipedia defined the term

In finance, the efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) asserts that financial markets are "informationally efficient", or that prices on traded assets (e.g., stocks, bonds, or property) already reflect all known information, and rapidly change to reflect new information. Therefore it is impossible to consistently outperform the market by using any information that the market already knows, except through luck. Information or news in the EMH is defined as anything that may affect prices that is unknowable in the present and thus appears randomly in the future.

The efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) often serves as the theoretical justification of putting all money in stocks index funds. The idea cost tremendous amount of money to 401K investors. Contrary to efficient market hypothesis (which, essentially, advocates cost averaging as the best thing since sliced bread) individual investors should pay attention to valuation metrics like price-earning (P/E) ratio. Shiller states that this plot "confirms that long-term investors—investors who commit their money to an investment for ten full years — did do well when prices were low relative to earnings at the beginning of the ten years. Long-term investors would be well advised, individually, to lower their exposure to the stock market when it is high, as it has been recently, and get into the market when it is low. This correlation between price to earnings ratios and long-term returns is not explained by the efficient-market hypothesis.

While the ideas of self-regulation and feedback loops are definitely applicable to economic systems, naive belief in "running equilibrium" which is what efficient market hypothesis is about led to serious policy mistakes not only in 401K investments but for the financial markets as a whole. One tremendously negative side effect was lax regulation of financial markets.

Susan Strange actually called the resulting social organization Casino Capitalism. As Sushil Wadhwani in the FT.com Insight column How efficient markets theory gave rise to policy mistakes (please remember that FT is a City publication and the bastion of conservative economic thinking) noted:

Clients frequently tell me they are puzzled that policymakers allowed such a significant crisis to develop. Their incomprehension is deepened by the recognition that, in recent years, many countries made their central banks independent, and these are typically run by people with formidable reputations as academics.

I wonder whether a common thread running through many of the policy mistakes is a belief in the efficient markets hypothesis (EMH).

Over the past decade, while the bubbles were emerging, it was frequently argued that central bankers had neither more information nor greater expertise in valuing an asset than private market participants. This was often one of the primary explanations for central banks not attempting to "lean against the wind" with respect to emerging bubbles.

As I argue in my recent National Institute article, it is likely that, had central banks raised interest rates by more than was justified by a fixed-horizon inflation target while house prices were rising above most conventional valuation measures, the size of the eventual bubble would have been smaller. At least as importantly, because of the fear of being seen as "market-unfriendly", fiscal and regulatory policy did not lean against the wind either. Our economies would plausibly have exhibited greater stability if tax policy had been used in an anti-bubble fashion (e.g. a counter-cyclical land tax) and if regulatory policy had been more activist (e.g. a ceiling on loan-value ratios) and contra-cyclical (e.g. time-varying bank capital requirements).

Once the recent bubbles burst in 2007, some central banks (including many of those in Europe) were surprisingly slow to cut interest rates, and this policy mistake may well lead the current recession to be longer and deeper than it might have been. One reason for their reluctance to cut interest rates was the significant rise in commodity prices. In relying on the EMH yet again, policymakers used longer-dated futures prices for these commodities in preparing their inflation projections. Their failure to allow for the then widely discussed possibility that a "bubble" had developed in the commodity markets thereby led them significantly to overestimate prospective inflationary pressures.

Recently the Nobel laureate George Akerlof has, with Robert Shiller, argued that Keynes's explanations for excessive financial market volatility and depressions relied importantly on the possibility that individuals can act irrationally and for non-economic reasons. However, modern-day "Keynesian" models of the economy typically ignore this essential insight and can therefore be a deficient tool for setting policy. Personally, I find this neglect of Keynes surprising as at least some fund management companies (including the hedge funds I help manage) assign an important role to this insight in their investment process.

This failure to incorporate the role of what Keynes described as "animal spirits" might well have permitted the naive belief that recapitalizing the banks would lead them to lend again. Once "confidence" has evaporated, banks will not lend however well-capitalized they may be. Unsurprisingly, governments are now having to explore other ways of making banks lend, and one has to wonder whether they might be driven to full-scale nationalization.

Of course, because of "animal spirits" one can find that monetary policy becomes surprisingly ineffective in slumps. Hence, although it is laudable the Bank of England has cut UK interest rates significantly in recent months, we should all have been much better off if it had reduced rates more pre-emptively. Now we will need so-called quantitative easing - with, perhaps, the Treasury guaranteeing assets acquired by the Bank.

This financial crisis should not have surprised anybody: financial history is littered with examples of bubbles, manias and crashes.

The main lesson is that our monetary, fiscal and regulatory policies must be designed to protect the many innocent people in the rest of the economy from the consequences of excessive financial market volatility.

(The writer is chief executive of Wadhwani Asset Management and a former member of the Bank of England's monetary policy committee FT Syndication Service)

The second problem with most publicly traded companies is that much of their business is a black box - without faith you have a hard time valuing the company since you can't see behind the curtains. That's true even if you work for the company and have access to some internal data. That means that situation is quite different from what is written about it in Money magazine and similar "feel good" publications. As Bill Fleckenstein The meddlers can't tame the market - MSN Money noted:

We have just come through a decade-plus in which the Fed intervened "successfully" enough so that folks came to look upon the stock market (and then the real-estate market) as pet kittens that spit out hundred-thousand-dollar bills. Markets are not like that at all. They are more like savage beasts looking to rip your head off.

The era of "pet markets" that effortlessly make people rich is definitely behind us.

When Vanguard PR people try to persuade you that "Whether you're an expert of not, it's human nature to imagine that have some unique insight into the market, something that's eluded everyone else" they forget to mention that this is perfectly applicable to the idea that S&P 500 outperforms bonds for a given period. Due to changes in S&P500 composition that is no scientific evidence for that and popular "proofs" usually presented smell data mining. The real reason for popularity of this hypothesis is that fees for stock funds are dramatically higher then for bond funds.

That does not mean that it does not make any sense to own stocks in 401K portfolio. Like a medicine they can be good in small doze. But current recommendation represent huge overdose. Moreover price earning ration still matters and for 401K investor it make sense to buy them only at depressed prices and then sell as soon as they reach elevated P/E ratios. Cost averaging does not make much sense outside short periods of depressed prices. It is stupid to buy overpriced junk on regular basis, no matter what professor Siegel recommends (and he does not eat his own dog food, his income and retirement savings are diversified with consultancy feed to high dividend mutual funds, books and other sources). Stocks for a long run is a huge gamble...

| It makes sense to own stocks in 401K portfolio. But in much smaller doze then usually recommended and if, and only if you can buy them at depressed prices and can sell them at elevated valuations. Cost averaging does not make much sense outside short periods of depressed prices. Stocks for a long run is a huge gamble... |

Buying diversified stocks fund is essentially equal to making a macro economy call. Making macro calls is tough. This is why so many investors do not rely on macro predictions and use stable value fund and TIPs in their 401K portfolio. And that's why so many 401K investors ended so poorly in 2008 losing on average 5% (after inflation) in their S&P500 portfolio for each year of the last decade.

| "I

have this threadbare rule that has worked very well for me, Your bond position should equal your age." John C. Bogle, the father of index investing |

First of all one of facts on the table is that 401K investors who invested in S&P500 from 1998 to 2008 and used strict cost averaging strategy ( and did not make any trades) are big losers. They and many other investors which used cost averaging into stocks funds were royally ripped off due to brainwashing that was dominant during the last ten years. And those losses are significant as of December 2008 the lost approximately 50% in comparison with those who used stable value fund (exact figure depends on fees in the S&P500 mutual fund they used, here is assume SPY or Vanguard Institutional Index fund). That means that if they have $100K in their 401K plan, then investors in stable value fund have $160K. Not a small difference by any metric. Real after inflation return for S&P500 was negative for the last ten years so those investors should actually be called donors as most 401K investors.

And that's not accidental. 401K investors are not going to get better because mega-corporations are run by managers who are in it for their own enrichment and shareholders have zero say. This is a classic principal-agent conflict.

That means that in no way cost averaging should be used for stock funds. You should buy them only at significant discount (let's say 25% or more off the 1000 days average). Those moments are rare (one in five-seven years) but 401K investors should be in no hurry to give money to Wall Street crooks.

Here is a couple of interesting comments from the discussion Stewart vs. Cramer Long-Term Asset Allocation Incorrectly Maligned -- Seeking Alpha

- zaar

I agree with 8financial. "Everything works until it doesn't"...is exactly right.

I disagree that Stewart went too far. Stewart was correct to slam the "stocks for the long run" mantra of the financial industry. It is worse than a crap shoot (if you don't know what you are doing or you hand your money over to someone else less interested in your future, i.e. an financial advisor). The fact that blind, long term investing has worked in certain markets for certain durations of time says nothing about the future. Due diligence and monitoring is required no matter what and I think that Stewart was correct in criticizing the deception and the empty money-for-nothing promises of the industry.

- silver-bug 23 Comments

Well, I think long term investing in this context (where a fund manager or a financial advisor "manages" your money) is overrated.

I agree with 8financial. "Everything works until it doesn't" is what's happening right now... and to quote Warren Buffett, "Only when the tide goes down will you know who's been swimming naked."

A lot of the fund managers have been acting like foxes watching over the hen-house, practically taking advantage of public who were willfully ignorant and acting like the owner of the hen-house giving the keys to the foxes willingly (I am placing blame on both the perpetrator and the victim). It works until it doesn't.

It is like the emperor who has been walking the streets naked. Once the hype is gone and the turd hits the fan, all hell breaks loose, and the public goes flailing around like headless chickens.

The bottom line is this: we are all in this together and there won't be victims unless we allow ourselves to be victimized. Ignorance and

complacency can harm us.

There are multiple reasons why stocks bought via cost averaging were a mousetrap for 401K investors for the last 15 years or so:

Reckless policy of Fed under Greenspan. Fed behavior under Greenspan was the catalyst which converted stock market into giant unregulated casino (that's actually how Europeans call London City, and events of 2007-2008 had shown that they have a point ;-) with hedge funds as the major players. The same was true for Wall Street. And house always wins: when the wave of credit expansion collapsed, this house of card collapsed too but financial management firms like Fidelity and Vanguard retained all the fees they collected from 401K donors. The latter lost 30-40% or more in cases of all stock portfolios.

Casino that stock market became in which stock movement signal nothing about the direction of the market and more about that fact that some hedge fund or other large players got in trouble or, vise versa, that they decided to make a huge bet.

Problems with the composition of S&P 500 index.

Massive stealing of funds (aka redistribution via bonuses) in all major financial corporations and many non-financial corporation by the top brass (new Gilled Age).

Inventive accounting, when financial statements did not reflect actual financial position of the company and are just a smoke screen designed to hide the problems.

Like intermediate term bonds are dangerous with yields below 5%, stocks that pay low dividends or no dividends are also very dangerous and are suitable only for trading not for "buy and hold" approach. Actually the ability of S&P500 pay, say, 3.5% in dividends might be a good point of buying into it. In "normal times" S&P500 paid very low dividends and that speaks against buying it via cost averaging program.

| Like intermediate term bonds are dangerous with yields below 5%, stocks that pay low dividends or no dividends are also very dangerous and are suitable only for trading not for "buy and hold" approach. |

It is interesting to note that in 2007 financials comprised more than 20% of the S&P 500 and investors in S&P500 suffered "oversized" for diversified index losses simply due to size this sector and the magnitude of the subprime problem. And this is not a single case.

If you look back at 2000, technology was over 20% of S&P 500, and whenever you get a sector that comprises so much of the market in a capitalization weighted index, it's usually a concern. That means there might be some inherent defects in S&P500 construction which amplify returns during the inflation of the bubbles and corresponding losses when the bubble burst (probably usage of capitalization weights is one such factor). We should be too surprised to see 50% haircut of S&P500 from the top 2007 value (around 1570 I think) at one point in 2008 or 2009.

|

There might be some inherent defects in S&P500 construction which amplify returns during the inflation of the bubbles and corresponding losses when the bubble burst |

If available, more broad based passive indexes based funds, for example, Vanguard Extended Market Index Instl (VIEIX) might be a slightly better bet (although the dose should be very small as evidentially this is the same, pretty toxic medicine in a different bottle):

The investment seeks to track the performance of a benchmark index that measures the investment return of small- and mid-capitalization stocks. The fund employs a passive management strategy designed to track the performance of the Standard & Poor's Completion index, a broadly diversified index of stocks of small and medium-size U.S. companies, which consists of all the U.S. common stocks traded regularly on the NYSE, AMEX, or OTC markets. It typically invests substantially all of assets in the 1,200 largest stocks in its target index, thus covering nearly 80% of the Index's total market capitalization.

But again stocks like alcohol should be used in moderation ;-). I think most 401K investors can greatly benefit from listening the interview by Professor Bodie in which he recommends TIPS instead of stocks to lower the level of retirement risk

Nov. 12 (Bloomberg) -- Zvi Bodie, a professor of finance at Boston University, talks with Bloomberg's Tom Keene about U.S. financial markets, investment in so-called TIPS, Treasuries and inflation-protected securities, and stock and corporate bond risk.

Listen/Download

He gives a very good advice: forget about all this naive hype about "stocks for a long run". Hype that smells Lysenkoism. Please use TIPS for "safe" part of your retirement. And ensure that this is the dominant part of your retirement portfolio as the last thing you want is to be underfunded due to taking excessive risk.

And chances of getting into such situation are very real as November 2008 demonstrated to so many baby boomers (those who did not learned lessons 2001-2003 bubble burst). Please, please do not believe in investment advisor hype... Take the investment risk extremely seriously and do not play with your retirement.

You already was ripped off by switching from defined benefit plans to defined contribution plans. There is no such things as safe investing in equities, especially in a long run. Idea that somehow investing in diversified stock portfolio is limiting your risk is a hogwash and contradict the fundamental of economics. You cannot avoid risk by using longer time horizon, because otherwise stocks should demonstrated equal or lesser then bonds returns "in a long run". If we assume that stocks return 4% above inflation they are at least twice more risky then TIPS which return just 2% above inflation. Any deviation from this contradicts the notion of risk premium. He also mentions that Excel gives to anybody with IQ a perfect tool for modeling your financial future: just put then numbers into it and see what will be your war chest when you turn 62.5 or 66 depending on your retirement plans. b If the current level of contribution guarantees comfortable retirement with TIPS or stable value of mix 50/50 why take additional risk? For what ? To feed brokers ? That does not make any sense... Treasuries can be bought directly outside 401K plans so you can really avoid paying to brokers (what what additional value that provide in case of TIPS in comparison with holding bonds to maturity ?).

So on any target date there in no certainty on what your stock portion of your portfolio will have a certain value. Again look at November 2002 and November 2008 for a very convincing proof.

The truth is that you should not use stocks as a dominant part of your 401K portfolio. Hedging is more important then diversification: the simplest way to decrease your risk is to invest larger part of your portfolio in safe assets. The fundamental idea of risk reward is how much you allocate to safe assets.

The short answer is yes. For longer answer see Protecting your 401K from Wall Street. It looks like baby boomers generation owns as part of their non-pension assets the largest percentage of stocks in the US history (The Difference Between Now and Then)

US households have been a key driver of the multi-decade US credit cycle. Again, circumstances of the moment are completely different than was seen at the last secular low of substance. As a very quick and powerful note, we need to remember that in early 1982, US households held very little in the way of equities. Today you can see the number stands at 17 % of household net worth, but we have to remember this is down from 25% a few years ago as a result of market value contraction since that time. Moreover, this number does not include IRA’s, 401(k)’s, etc.

The baby boom generation has been the generation of equity ownership, starting with very little exposure to now significant exposure (inclusive of the qualified plan money). This will not repeat itself again and was a key demand driver of the last three decades.

And God knows what percentage in 401K account. Can be as high as 57% on average, if we consider the losses (11% vs. 19% of S&P500) suffered by 401K plans in the first three quarters of 2008 (faq_myths_about_401k)

All retirement plans—DC plans, defined benefit (DB) plans, state and local government retirement plans, and IRAs—are long-term savings vehicles and invest a large share of their assets in equities. Thus, they all have suffered in the market turmoil. The latest data available, from the first three quarters of 2008, show that the assets of private-sector and state and local government DB plans were down 14 percent, and IRA assets were down 13 percent. Assets of 401(k) plans fell somewhat less, by about 11 percent, and 403(b) plan assets were down 10 percent over the first three quarters of 2008. Over the same period, the S&P 500 total return index was down 19 percent.

I think that ICI is fudging statistics and real losses are higher than 11% for the first 3Q of 2008 (Fidelity 401(k) Balances Down 27 Percent - Planning to Retire (usnews.com) ). For example, In 1999 just before the burst of dot-com bubble the percentage was 72%. which corresponds to 14% of losses (401(k) Accounts Are Losing Money for the First Time).

The average 401(k) account had 72 percent in stocks and stock funds in 1999, according to the latest data available from the Employee Benefit Research Institute, a Washington nonprofit group.

Moreover around 6 percent of assets in 401(k) plans were shifted out of stocks and into bonds last year, mostly during tumultuous October and November, according to an analysis by human resources consultant Hewitt Associates. The percentage of 401(k) participants holding 100 percent equities dropped from 20 percent at the end of 2007 to 16 percent at the conclusion of last year. (In 2000, 37 percent of participants had 100 percent of their 401(k) in equities.) Those people, especially baby boomers, losses are real (It's Time To Take Stock of 401(K)s)

"If you're 60 years old and lost 30 percent of your 401(k) account balance, it is time to re-plan your retirement," said Wray, who believes companies must be honest and open in communicating this to workers. "You can't sugarcoat this, because the alternatives are to save a lot more, retire on less, or work longer."

|

A Ponzi scheme is a fraudulent investment operation that pays returns to investors from their own money or money paid by subsequent investors rather than from any actual profit earned. It might be that modern stock market dominated by hedge funds is closer to the definition of a Ponzi scheme then most 401K investors assume... |

During the Internet bubble, as well as the subprime fiasco, the only real fools were the people who left their money in too long. And that means retail and 401K investors brainwashed by "long run" propaganda. One can reasonably argue that since Internet bubble and into the real-estate boom the regulators were missing in action and the highest-paid bankers ditched all moral and ethical considerations to prop bogus stocks and radioactive investment schemes. Financial Ponzi schemes became the ultimate American product -- a lucrative enterprise for those up in the suites, and a disaster for everyone else. Like in any Ponzi scheme the last people who enter it are holding the bag.

The key problem is that most "longrunners" does not take into account valuation and that means they subject themselves to increased risk due to buying stock at or close to the top when Ponzi is about to burst into flames [Banned at Motley Fool!]

Why is this approach so controversial? Because it is rooted in the common sense idea that stocks, like all other assets, offer a better long-term value proposition when purchased at reasonable prices than they do when purchased at extremely high prices. At every place at which I have discussed Valuation-Informed Indexing (which I developed with the help of the hundreds of Financial Freedom Community members who offered constructive input during The Great Safe Withdrawal Rate Debate before further discussions were banned), I have seen two reactions to it.

Ordinary investors see quickly the merit of the idea of taking valuations into account, and are eager to learn more. Big Shots who have written books or published studies or calculators or web sites see this new approach as a threat to their status as Grand Poohbahs and cannot stand the idea of others talking about it and learning about it and further developing the concept by doing so.

That means that avid "longrunners" might later become disillusioned with the returns offered by stock indexes purchased at high valuations and suddenly realize that there are times when buy-and-hold investing (and, especially, cost averaging investing) is not nearly so exciting as it has been advertised by Jeremy Siegel and similar "gurus".

Being simple and attractive (albeit questionable) approach to 401K investing Siegelism proved to be remarkably resilient in years after dot-com bubble burst. That makes it somewhat similar to many high demand sects when failure of the key prophecy insread of driving people out of the sect makes them more cohesive and more defensive about hier failed doctrine.

Also euphoria of high returns is highly contagious disease. As one of my friends, who uses all stock portfolio in his 401K noted in September 2007 "I am still up 10% this year and what about you ?" And I feel really bad about my 4% return. And at this point it was not known to me or him that the next year he will be down 25% and I up 3%. To quote Upton Sinclair "it is very hard to get someone to understand something when their self-esteem depends on remaining naive."

There were 30 defined bear markets on the Dow. Ten worst have declines over 30% and include one with the decline of over 80%. All those can break the resolve to continue buy and hold strategy and sell at the bottom which makes total return for many 401K investors negative. If my friend will be forced to retire the next year and this year will mark the start of the sharp recession then 30% decline will wipe out 30% of his savings. He is over 50 and that's the risk he takes. The question is "Is this risk necessary, is it prudent or it is the result of brainwashing?"

While one day crashes grab the headlines, they are not that dangerous as market recovers pretty soon. At least partially as happened in 2011 when S&P500 again crossed 1300 mark. The real danger is the a crash can force "longrunners" to sell in the most inopportune moment -- at the bottom like happened with many 401K investors who were close to retirement in 2003. But crash of 1929 extended into a bear market lasting almost throughout the 1930s and only ended by World War II. It lasted over 10 years and it took more then 20 years for stock fully recover compensating those who bought exactly at the peak. See BBC NEWS Business Market crashes through the ages for more information.

Also interesting is testimony of Robert Kutter before the Committee on Banking Services. This is not typical yellow financial press alarmist "blah-buster". The author is professional who speaks to professionals and he sees some deep analogies between the current situation and the situation in 1920s.

Testimony of Robert Kuttner

Before the Committee on Financial Services

Rep. Barney Frank, Chairman

U.S. House of Representatives

Washington, D.C.

October 2, 2007

Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee:

Thank you for this opportunity. My name is Robert Kuttner. I am an economics and financial journalist, author of several books about the economy, co-editor of The American Prospect, and former investigator for the Senate Banking Committee. I have a book appearing in a few weeks that addresses the systemic risks of financial innovation coupled with deregulation and the moral hazard of periodic bailouts.

In researching the book, I devoted a lot of effort to reviewing the abuses of the 1920s, the effort in the 1930s to create a financial system that would prevent repetition of those abuses, and the steady dismantling of the safeguards over the last three decades in the name of free markets and financial innovation.

The Senate Banking Committee, in the celebrated Pecora Hearings of 1933 and 1934, laid the groundwork for the modern edifice of financial regulation. I suspect that they would be appalled at the parallels between the systemic risks of the 1920s and many of the modern practices that have been permitted to seep back in to our financial markets.

Although the particulars are different, my reading of financial history suggests that the abuses and risks are all too similar and enduring. When you strip them down to their essence, they are variations on a few hardy perennials – excessive leveraging, misrepresentation, insider conflicts of interest, non-transparency, and the triumph of engineered euphoria over evidence.

The most basic and alarming parallel is the creation of asset bubbles, in which the purveyors of securities use very high leverage; the securities are sold to the public or to specialized funds with underlying collateral of uncertain value; and financial middlemen extract exorbitant returns at the expense of the real economy. This was the essence of the abuse of public utilities stock pyramids in the 1920s, where multi-layered holding companies allowed securities to be watered down, to the point where the real collateral was worth just a few cents on the dollar, and returns were diverted from operating companies and ratepayers. This only became exposed when the bubble burst. As Warren Buffett famously put it, you never know who is swimming naked until the tide goes out.

There is good evidence — and I will add to the record a paper on this subject by the Federal Reserve staff economists Dean Maki and Michael Palumbo — that even much of the boom of the late 1990s was built substantially on asset bubbles. ["Disentangling the Wealth Effect: a Cohort Analysis of Household Savings in the 1990s" [PDF]]

A second parallel is what today we would call securitization of credit. Some people think this is a recent innovation, but in fact it was the core technique that made possible the dangerous practices of the 1920. Banks would originate and repackage highly speculative loans, market them as securities through their retail networks, using the prestigious brand name of the bank — e.g. Morgan or Chase — as a proxy for the soundness of the security. It was this practice, and the ensuing collapse when so much of the paper went bad, that led Congress to enact the Glass-Steagall Act, requiring bankers to decide either to be commercial banks—part of the monetary system, closely supervised and subject to reserve requirements, given deposit insurance, and access to the Fed's discount window; or investment banks that were not government guaranteed, but that were soon subjected to an extensive disclosure regime under the SEC.